- Home

- Kody Keplinger

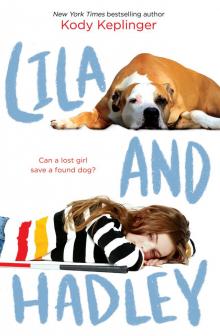

Lila and Hadley

Lila and Hadley Read online

For Corey,

the dog that changed my life

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

The Swift Boys & Me Preview

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

“I really ain’t a dog person.”

Mama always says I shouldn’t say ain’t. Says it’s not proper grammar. But then, she’s also the one who taught me that stealing is wrong, and now that’s what she’s in jail for. So as far as I’m concerned, she don’t got a leg to stand on.

“Did you hear me?” I ask Beth as she puts her tiny car into park and shuts off the engine. “I said I ain’t a dog person.”

“That’s all right. You don’t have to touch the dogs. Don’t even have to look at them if you don’t want. We’ll only be here for a few minutes.”

“Then let me stay in the car.”

“No way. It’s ninety degrees!”

“You got air-conditioning.”

Beth shakes her head. “Out of the car, Baby Sister. You’re coming inside. But I promise, it won’t take me long. Then we can go back home.”

“Hadley.”

“What?”

“My name ain’t Baby Sister. It’s Hadley.”

I don’t gotta look at Beth to know I’ve hurt her feelings. But I don’t care. She’s got no right to call me her sister. Not after the way she left us five years back. Three days ago, when she picked me up from Mama’s house, was the first time I’d seen her since I was seven and she was nineteen. We might share blood, but we sure ain’t family.

“Okay, Hadley,” she says, her voice quiet. I hear the click as she unbuckles her seat belt. “Let’s just go inside.”

“But I ain’t a dog person.”

She ignores me this time and climbs out of the car. For a second, I think about staying put. It’s not like she can drag me out of the car if I don’t wanna move. Not without making a real big scene.

But June in Kentucky sure ain’t nothing to sneeze at, and Beth’s already turned off the car and taken the keys with her. My not wanting to melt into the scorching, cracked fake-leather seat wins out over my not wanting to go inside.

“Do you need my arm?” Beth asks as I slam the passenger-side door as hard as I can. “Can you see all right?”

“I’m fine,” I snap. But as soon as the words leave my mouth, my foot collides with the edge of the curb. I start to fall forward, and Beth grabs hold of my elbow and keeps me upright. Once I’ve got my balance again, I yank away from her. “I said I’m fine.”

Beth huffs out a breath, but she don’t argue. “All right. Come on, then.”

I follow close behind her, keeping my eyes down so I can watch for bumps or steps I might miss as we make our way down the sidewalk and onto a path that leads to a large brick building. When I’m looking right at something, I can mostly see all right. But it’s the edges where I get tripped up. Anything out to the sides or below or above a certain point is just … gone. It’s not darkness or black spots or anything. It’s like my brain tries to fill in what ought to be there, so sometimes I think I can see but … I can’t. And those edges have been creeping in slowly for years. The doctors say I’m already what they call “legally blind.” And one day that tunnel of clear vision will be more like a pinprick.

I don’t like to think about that if I can help it.

Beth reaches the big front door, and I can already hear a bunch of dogs barking inside before she’s even pulled it open. She gestures for me to walk in ahead of her. I do, but I keep my arms crossed tight over my chest so she knows I ain’t happy about being here.

Beth walks to the front desk. There’s a tall teenage girl with a round, pale face sitting behind it, talking to an older, bearded man who’s clutching a fluffy white dog in his arms.

“Thank you so much, Angela,” the man says. “Sprinkles is going to have a good home with me.”

“I’m sure she will, Mr. Xu,” Angela says. “Be sure to post lots of pictures and tag Right Choice Rescue on social media, okay? We love seeing how our dogs do in their forever homes.”

“I certainly will. Or, well … my granddaughter will. She says I’m bad at taking pictures.” He laughs, says goodbye to Angela at the desk, and leaves, his sandals squeaking against the tile. “Let’s go, Sprinkles,” I hear him say before he’s out the door. He’s using that squished, goofy voice people use when they talk to pets. “We have to go buy you some new toys, yes we do.”

Beth steps up to the desk then. “Hurray for a successful adoption!”

“Thanks to you,” Angela replies, tucking her short red hair behind her ear. “You worked miracles getting Sprinkles housebroken.”

“Some dogs are a little more stubborn than others,” Beth says. “You just have to be patient … and have the right dog treats.” She glances over at me, still standing several feet back. “Angela, this is my little sister, Hadley. She’s going to be living with me for a while.”

“Oh, hi there,” Angela says, voice bright and friendly.

All I do is shrug.

“Is Vanessa in her office?” Beth asks.

“She should be.”

“Great. Thanks, Angela.”

Beth walks back over to me as the door opens and a couple comes in pushing a stroller, heading straight for Angela’s desk.

“I’ve just gotta go back to Vanessa’s office and pick up my check,” Beth tells me. “Then look in on a few of the dogs. You can either stay here or walk around if you want. I’ll come find you when I’m done, okay?”

Shrug.

Beth sighs again. I make her sigh an awful lot.

I stand there for a while after she walks off, but eventually watching Angela chatting with the couple—who seem very particular about the kind of dog they wanna adopt—gets real boring. So I decide I might as well walk around.

To the left of the desk there’s a door that opens onto a hallway. I walk down it until I reach an intersection and head right. A second later, I find myself in a large room full of dog pens. The pens are pretty big, too, giving the dogs lots of room to walk around inside. I must’ve wandered into the large dog section, I realize, because all the dogs I pass seem huge.

There are dogs in every shape and color. Pointy ears, floppy ears. Dogs with curly hair and dogs with sleek straight fur. Black dogs, white dogs, yellow, spotted. Most of them come to the edge of their pens as I pass, wagging their tails all excited, like I’m here to see them. A few even jump up, paws on the bars, barking. Not scary barking, but like they want my attention.

I walk past all of them.

It’s not that I dislike dogs. They’re fine, I guess. But we never had one, so I don’t get all worked up about them the way a lot of people seem to. I ain’t got a clue where Beth gets her love of them from, but she likes them enough that she became a dog trainer. I wonder if she was a dog person when she lived with Mama and me or if that happened after she left us.

I walk past pen after pen, ignoring the dogs inside, until something makes

me stop.

I’m standing next to one of the kennels, but the dog inside ain’t up at the edge, trying to get me to notice it like the others. Nope. For a minute, I don’t see a dog at all, and I think this one might be empty. But then I lower my eyes and see a large brown-and-white lump on the floor. It’d been just outside my range of vision before.

It’s a pretty big dog. Real broad and stocky-looking, with high set, smallish ears that flop down at the tips. And its head is huge, flat with a big jaw. Its face is mostly white but with a big brown spot covering most of the left side. I don’t know dog breeds real well, but I think I’ve seen dogs like this on TV. Pit bull, I’m pretty sure.

The dog’s just lying there, eyes open, and all I can think is that it looks like how I’d look if I were a dog. Downright miserable. Like it’d rather be anywhere else.

I don’t know what makes me do it—I sure didn’t plan to—but I find myself crouching down in front of the kennel. And then I’m talking to the dog.

“Hey,” I say.

It doesn’t move, but I think its eyes are looking my way.

“Bad day?” I ask, as if the dog can answer. And I don’t know, maybe it kinda does. Its face certainly looks like it’s saying, “Yes. Terrible day.” I nod at it. “Me, too. A whole lot of them lately.”

Slowly, I reach my hand through the bars. I know Beth would probably tell me this ain’t safe—I don’t know this dog or what its temper is like—but I do it anyway. I move my fingers in a beckoning gesture. For a minute, I don’t think the dog’s gonna come to me. Not like I blame it. I didn’t wanna move from my bed today, either.

It takes a second to make up its mind, but it starts to stand. It moves toward me real slow, as if second-guessing every step. I ain’t sure what comes over me, but I hear myself cooing to it, softly saying, “Good dog. There we go. Come on.” And silly as it might be, it works.

The dog reaches me at last. It stares at my face for a minute. Its eyes are real big and brown and … sad. That’s the only way I know how to describe them. Sad and maybe … lonely? Then it lowers its huge head to sniff my palm. Once it’s done checking me out, I reach up and scratch behind one of its ears.

And then we both let out this sigh. Right at the same time. Like whatever has just happened has lifted a weight. Like we’re both relieved.

That’s how I meet Lila.

When Mama first told me I’d have to go live with Beth, I thought she was pulling my leg. Until she started crying, that is.

Things had been weird for the past year or so. First, Mama had stopped working as Dr. Parker’s bookkeeper and gotten a new job cleaning houses, though she wouldn’t tell me why. She’d been working for Dr. Parker for years, taking care of all the billing and keeping track of the money for his practice. So I kinda figured something was up when she wasn’t working for him no more. Then she was always on the phone with people, and when she’d hang up, she’d be all upset and teary-eyed. When I asked who she was talking to, she told me it was a lawyer, but she said I didn’t need to worry about it. She started being real forgetful, never remembering when parent-teacher conferences were, or forgetting to go to the grocery store when we ran out of milk or toilet paper or stuff like that. I’d press her about it sometimes, but she just said she was stressed out and that everything was gonna be fine.

“Don’t worry, Bean,” she’d say, stroking the back of my head. “It’s nothing for you to get upset over. It’ll all be okay.”

Turns out, my mama is a liar.

She’d lied to Dr. Parker for months while she was stealing money from him, and she’d lied to me every time she said things would be fine. They weren’t fine at all. The judge had found her guilty in May, and she was going to jail for a whole year, and now she was telling me I had to go live with my stupid older sister who I hadn’t even seen since I was seven.

“I’m sorry, Hadley,” Mama said, her voice muffled by the trembling hands pressed against her face. “I’m so, so sorry. But … but you’ll be okay, I promise. I— Hadley?”

I’d already stormed off. And I made sure to slam my bedroom door real hard, too. She’d lied to me so much. Why should I believe her promises now?

I wasn’t just mad about what she’d done or about having to live with stupid Beth. It was all of it. I’d just finished sixth grade, and I was gonna have to switch schools come August. Beth lived in Kentucky, but I’d spent my whole life in Tennessee. Mama kept saying it was only a three- or four-hour drive, but that’s a long way. Far enough that I didn’t know when I’d see my friends again after I left.

So no, I wasn’t gonna be fine.

I refused to talk to Mama for the next two days, even as she helped me pack up my room. Once Beth came to get me and Mama went to jail to serve her sentence, this house wouldn’t be ours anymore. We were just renters, and that meant our landlady, Mrs. Martindale, would be letting new people move in. My bedroom would be someone else’s bedroom. And I’d be living in a new state, in a new house, going to a new school …

And it was all Mama’s fault.

She tried to trick me into talking to her. She made my favorite dinner—pulled pork sandwiches—and offered to let me stay up late to watch TV, but I didn’t have nothing to say to her. And when Beth showed up in her little blue car to take me away, I walked out the front door without even saying goodbye.

“Hadley,” Mama had called, and I could hear her voice breaking. She was about to cry again. Just like she’d done the day before. And the day before that. “Bean, please …”

Beth glanced at me. She hadn’t said a whole lot since she’d gotten there. But she asked, “Don’t you wanna say goodbye?”

“No.”

I also didn’t wanna hear Beth’s opinion on any of it. She didn’t have a right to talk to me about saying goodbye. She hadn’t said goodbye to me when she’d left us. One day she’d been there, teaching me how to do a French braid and painting my toenails in the bright blues and purples that Mama hated. And the next she’d just been gone. Walked out on us. So who was she to talk about goodbyes?

“But you know Mama won’t be back for a while.”

“I don’t care,” I snapped.

Beth looked over at Mama then. It must’ve been the first time they’d really looked at each other since Beth left us all those years before. But Mama just shook her head. I went and climbed into Beth’s car, slamming the passenger-side door, while she and Mama exchanged a few quiet words. Then Beth got into the driver seat next to me.

“You ready to go?” she asked.

I didn’t answer. What did Beth want me to say? Of course I wasn’t ready. I didn’t wanna go anywhere. I didn’t wanna live with her. I didn’t want any of this. Mama had spent years teaching me the difference between right and wrong, and now she was the one who’d done something real wrong, and I was being punished, too. It wasn’t fair.

Beth started the engine, but before she pulled out, there was a tap on my window. Mama stood outside, gesturing for me to roll the window down.

I didn’t move, so after a minute, Beth rolled it down for me.

“Hadley,” Mama said. Yep. She was crying. I wanna say it didn’t make me feel bad for her. But it did, just a little.

Mama had never been much of a crier before all this. In fact, I’d only seen her cry three times before she stopped working for Dr. Parker. The first time was at Grammy Lora’s funeral, when I was four. The second was two years later, the night the police officer showed up to tell her that Daddy had been in a car accident and wasn’t coming home. And then, of course, the day Beth moved out.

But she’d been crying an awful lot over the past few months, and especially in the two days since she’d told me the judge’s decision. He’d given her a few days to “get her affairs in order”—whatever that meant—before she’d have to go to jail. That’s where she’d be spending the next year because of what she did. And as much as I wanted to punish her, too, seeing her hurt still hurt me a little bit.

“H

adley,” she said again, reaching through the open window to squeeze my shoulder. “I love you, Bean. You know that, right? No matter what happens, I love you so much. And I’m sorry. But I’ll see you soon, okay? I’ll write to you. And Beth can bring you to see me … Right, Beth?”

“Sure,” Beth said. “Any time Hadley wants me to bring her for visitation, I will.”

“You hear that, Bean?”

I didn’t answer.

Mama swallowed hard. “Okay. Well … be careful. Take care of yourself. I love you.”

“I’ll take care of her, Mama,” Beth said. “I promise, she’ll be fine.”

That’s when I decided Beth was probably a liar, too.

I was angry and heartbroken and scared. I didn’t know if I’d ever be “fine” again.

Beth and I finally pulled away. And even though I didn’t want to, I caught myself staring in the side mirror, watching Mama still standing in the driveway, hands over her face, until I couldn’t see her no more.

Which, I guess, didn’t really take all that long.

“So,” Beth said after about an hour of driving. She’d been talking basically nonstop. Just “trying to fill the silence” as Mama would have said. Talking about her job as a dog trainer and her clients and also the dog rescue she’d been working with and the house she lived in and the school where I’d be going in August. Talk, talk, talk. But then her voice had turned a bit nervous. “Mama told me your eyes have been getting worse. Because of the … shoot. What was it called again? RP stands for … uh …”

“Retinitis pigmentosa,” I muttered. I hated those two words. They sounded harsh and ugly, and I’d heard them a million times in the past couple years. Usually by eye doctors who said it in that serious I-have-bad-news voice.

“That’s it,” Beth said. “Thank you. Anyway, I was talking to Mama about it, and I got to thinking, maybe it’s about time you start making some preparations. For when it gets worse, you know? Mama said she’d been meaning to look into different programs or classes that could help you, but with everything going on she hadn’t had a chance. So I did some research, and we could get you a teacher. Someone to show you how to walk with a cane and cross streets safely. That kind of thing. We might even be able to find you a Braille teacher if that was something you’d be interested in. What do you think?”

A Midsummer's Nightmare

A Midsummer's Nightmare Shut Out

Shut Out Lying Out Loud

Lying Out Loud Run

Run The DUFF: Designated Ugly Fat Friend

The DUFF: Designated Ugly Fat Friend The Swift Boys & Me

The Swift Boys & Me Lila and Hadley

Lila and Hadley Secrets and Lies

Secrets and Lies Duff

Duff That's Not What Happened

That's Not What Happened